Pregnant Women Giving Birth to a Baby Fome the Frunt Vowu

- Research commodity

- Open Admission

- Published:

The influence of women's fearfulness, attitudes and beliefs of childbirth on way and experience of birth

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 12, Article number:55 (2012) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Background

Women's fears and attitudes to childbirth may influence the maternity intendance they receive and the outcomes of nativity. This study aimed to develop profiles of women according to their attitudes regarding birth and their levels of childbirth related fear. The clan of these profiles with mode and outcomes of nascence was explored.

Methods

Prospective longitudinal cohort pattern with self report questionnaires containing a fix of attitudinal statements regarding birth (Birth Attitudes Profile Calibration) and a fearfulness of nascence scale (FOBS). Significant women responded at 18-xx weeks gestation and two months later on nascence from a regional surface area of Sweden (n = 386) and a regional area of Australia (n = 123). Cluster analysis was used to identify a set of profiles. Odds ratios (95% CI) were calculated, comparing cluster membership for state of care, pregnancy characteristics, birth feel and outcomes.

Results

Three clusters were identified – 'Cocky determiners' (clear attitudes virtually birth including seeing it as a natural procedure and no childbirth fright), 'Take it as information technology comes' (no fear of nativity and low levels of agreement with any of the attitude statements) and 'Fearful' (afraid of birth, with concerns for the personal impact of birth including pain and command, prophylactic concerns and depression levels of agreement with attitudes relating to women's freedom of choice or birth every bit a natural process). At eighteen -xx weeks gestation, when compared to the 'Self determiners', women in the 'Fearful' cluster were more probable to: prefer a caesarean (OR = 3.three CI: 1.6-6.8), hold less than positive feelings well-nigh beingness significant (OR = iii.half dozen CI: ane.four-nine.0), written report less than positive feelings most the budgeted nascence (OR = vii.2 CI: 4.four-12.0) and less than positive feelings virtually the beginning weeks with a newborn (OR = 2.0 CI 1.two-3.6). At 2 months postal service partum the 'Fearful' cluster had a greater likelihood of having had an elective caesarean (OR = 5.iv CI 2.1-fourteen.ii); they were more than likely to have had an epidural if they laboured (OR = 1.ix CI ane.one-three.2) and to experience their labour pain every bit more intense than women in the other clusters. The 'Fearful' cluster were more likely to report a negative feel of birth (OR = 1.vii CI 1.02- 2.9). The 'Accept it as it comes' cluster had a higher likelihood of an elective caesarean (OR 3.0 CI i.one-eight.0).

Conclusions

In this study 3 clusters of women were identified. Belonging to the 'Fearful' cluster had a negative upshot on women's emotional wellness during pregnancy and increased the likelihood of a negative nascence feel. Both women in the 'Take it equally it comes' and the 'Fearful' cluster had higher odds of having an constituent caesarean compared to women in the 'Self determiners'. Understanding women'due south attitudes and level of fear may help midwives and doctors to tailor their interactions with women.

Background

Understanding and responding to women's beliefs and attitudes during the childbearing period is an important focus of international motherhood wellness policy. The terms 'woman centred care' and 'informed choice' reflect that in add-on to the physiological aspects of pregnancy and nativity, there are psychological, psychosexual, and psychosocial aspects unique to the private life experiences of significant women. These must be considered in gild to optimise a woman's birth outcomes and experience [one]. The psychosocial wellbeing of women is now viewed as equally important as her physical wellbeing [2].

In a 'woman centred' approach the clinician moves beyond medico/protocol/risk centric care and seeks to amend understand the individual woman through ascertaining her attitudes to pregnancy and nativity and her particular life situation [3]. Attitudes have been conceptualized using a three-component model: affective, cognitive and behavioural [4]. The affective component consists of positive or negative feelings toward the attitude object; the cognitive function refers to thoughts or behavior; and the behavioural element represents the actions or intentions to act upon the object. Social psychologists differentiate a belief from an attitude by suggesting that a belief is the probability dimension of a concept – 'is its beingness probable or improbable?'[v] An mental attitude on the other hand, is the 'evaluative' dimension of a concept. 'Is it good or is it bad?' [5]. A modify in attitude toward a given concept can result from a change in belief well-nigh that concept [v].

The 'Harsanyi Doctrine' [half dozen] asserts that differences in individuals' beliefs can exist attributed entirely to differences in information [7]. Applying this doctrine to maternity care, it is interesting to consider where, what, how and past whom, information is shared between women and their care givers and what bear on this may have on their beliefs and attitudes. A recent report of 1,318 low-take a chance Canadian women conducted by the University of British Columbia and the Kid & Family Enquiry Constitute [8, ix] illustrates this point. Focusing on attitudes to birth technology, the Canadian study reported that women attention obstetricians were more favourable to the use of birth engineering and were less appreciative of women's roles in their ain nascency. In dissimilarity, women attending midwives reported less favourable views toward the use of technology and were more supportive of the importance of women'southward roles. Family practice patients' opinions fell between the other two groups. These women could be a cocky selecting population who cull a particular care giver according to their pre-existing attitudes, or alternatively the attitudes of the women could be influenced by the information they receive from their caregiver.

The determinants of a woman'due south attitudes and beliefs are inherently linked to cultural and health system specific influences [10]. In chance-averse biomedical systems of care the woman's attitudes and beliefs about birth may determine the level of intervention that she actively chooses or passively receives. With the aim of examining changes over fourth dimension (1987-2000) in women's expectations and experiences of intrapartum care, the Greater Expectations Study [11] surveyed approximately 1400 significant women beyond several wellness services in the United Kingdom (Great britain). It demonstrated that women's attitudes and expectations had shifted over the thirteen year period from when the original study [12] had been undertaken. The findings showed a human relationship between childbirth outcomes and women's antenatal attitudes. The consequence of greatest concern to the authors was the increase in women's antenatal anxiety about pain and their reduced organized religion in their power to cope with labour [eleven]. Over the same time period there was an increased use of obstetric interventions, particularly induction, epidurals and caesarean sections. Mean scores on a scale designed to measure a willingness to take interventions ('attitude to intervention') were significantly higher in 2000 than in 1987. Women who went on to have unplanned caesarean sections or assisted deliveries had significantly higher 'mental attitude to intervention' scores antenatally than women who went on to have unassisted vaginal deliveries. The report suggested that an caption for this was an increased use of epidurals past women who were positive nigh interventions [thirteen]. In 2001 an audit report was tabled in the UK as an investigation of the patterns of, and the reasons for, caesarean [fourteen]. This written report included women's responses to a range of attitudes and beliefs about childbirth. The findings indicated that women who preferred caesarean equally the fashion of birth held attitudes reflecting a belief that birth was not a natural process and that they were concerned near control and pain and safety.

In clinical practice 'woman centred care' and 'informed choice' have manifested in such practices every bit the distribution of evidenced based information brochures, client-held medical records, birth plans and formal screening for psychosocial pathology- in particular perinatal low and domestic violence [15–xix]. Despite the rhetoric, women'south individual circumstances, attitudes, beliefs and choices are not necessarily at the centre of the decisions fabricated in regard to her care. The term 'woman centred care' is not a commonly used term in Swedish motherhood policy. Women'southward personal autonomy is politically important, but the concept of 'informed choice' is limited by the State– for example under the universal state funded health system women take no freedom to choose their model of motherhood care nor mode of birth [20]. In Commonwealth of australia, choice is oft limited by the region where a woman accesses care [21].

In addition to the diagnosis of perinatal low, researchers and clinicians are increasingly recognising the importance of pregnancy-specific anxiety, with fearfulness of childbirth being a sub construct of this feet [22]. A clinically significant fright of childbirth is estimated to affect xx to 25% of significant women and the prevalence of severe fear that impacts on daily life is thought to be between 6 and 10% [23–31]. Nigh of the literature regarding childbirth fear has been focused on Scandinavian populations, however childbirth fear crosses cultural boundaries as studies from Commonwealth of australia [28, 29], the UK [xxx], Switzerland [31], Us [32] and Canada [23] attest. In an effort to empathise a woman's attitude or belief about birth information technology is important therefore to add the bear upon of fear to proceeds a fuller movie.

In 1985, Raphael-Leff published profiles of pregnant women [33] where she described mothers in four categories: 'Facilitator', 'Regulator', 'Reciprocator', and 'Conflicted' (Table ane). Her model, which is based on her extensive clinical experience, mother-kid observations and survey information, postulates that at that place is a diversity of approaches to pregnancy and early on motherhood within and betwixt societies. She describes these equally 'orientations' and, while other studies have linked particular personality traits to phenomena such as a request for caesarean for non medical reasons [34], Raphael-Leff states clearly that her model is not about personality traits. Different pregnancies and differing circumstances mean that a adult female'southward orientation may change with each gestation [33, 35].

A recent prospective report from Kingdom of belgium [36], attempted to predict a woman's childbirth experience using antenatal expectations of birth and the Raphael-Leff model of orientations. While the antenatal expectations of the women conspicuously predicted their postpartum recollection of intrapartum experiences, the study did not support the independent contribution to birth feel of the Raphael- Leff orientations after obstetric complications were taken into account. There was a suggestion however, that maternal orientations made some contribution to the childbirth feel.

To aid clinicians in their efforts to sensitively and finer place women at the heart of maternity care, more noesis is required well-nigh how women think most birth and the extent to which they are fearful. Further empirical research therefore is needed to better understand attitudinal profiles in pregnant women and the association this has with their pregnancy effect and feel.

In this study we aimed to identify profiles of pregnant women based on their attitudes to and beliefs virtually birth and their levels of childbirth related fearfulness. Nosotros aimed to compare pregnancy characteristics, outcomes and experiences of birth between these profiles. Our hypothesis was that women with an elevated fear of birth would emerge equally a distinct contour that had poorer pregnancy and birth outcomes than other women.

Method

This prospective accomplice study is part of a broader longitudinal investigation of aspects of pregnancy, nascence and early parenting. The information collection constitutes a sample of rural and regional women in Sweden and Australia undertaken during the years 2007 – 2009.

Participants

The Swedish cohort was drawn from a regional area in the province of Vasternorrland and the Australian cohort came from a northeast regional expanse in the land of Victoria. Both sites have an annual birth rate of around five hundred per twelvemonth and a largely homogenous population of not immigrant women. The Swedish group was recruited at routine ultra sound screening in pregnancy week 17-19. Almost all women undertake this examination in Sweden [37], making it an ideal fourth dimension to admission potential participants. A letter of the alphabet with information about the study was sent two weeks prior to the examination. Swedish speaking women with a normal ultrasound were approached by a recruiting midwife and asked if they wanted to participate in the study. The questionnaire was either filled out at the ultrasound ward, or completed at dwelling and returned by a paid postal envelope. In the Australian setting, all women who give birth at the local hospital attend a booking with a midwife at the antenatal dispensary between 18 -twenty weeks gestation. At this visit those women who were English speaking with a normal 18 week ultrasound result (thus reducing the chances of women with serious foetal anomalies being sent questionnaires) were invited to accept function in the study by the booking midwife. Those who agreed received written information, signed a consent form, and were given a questionnaire to either complete on the spot, or take habitation and return in a reply paid postal envelope. Reminder letters were posted on ii occasions to not responders in both settings.

Ethics approval was obtained from respective regional ethics committees in northern Sweden and Wangaratta, Australia besides as from the Mid Sweden University, and The Academy of Melbourne.

Questionnaires

Data was nerveless using cocky written report questionnaires equally part of a larger study, investigating women's' experiences of pregnancy and nativity. In the study reported here data is from 18 -xx weeks gestation and two months after birth. This study includes data from women who answered questions at both time points.

The questionnaire at eighteen-twenty weeks measured attitudes and beliefs regarding birth past determining the strength of women'south agreement/disagreement on a six-point rating scale to twelve personal and four full general statements which had been used previously in two big studies from the UK [xiv, 38]. The sixteen attitudinal items were subjected to factor analysis – reported in a previous study [39]. Four subscales were identified: 'Personal impact of birth', 'Nascence equally a natural result', Freedom of choice' and 'Safety concerns'. As the iv subscales are brusque (less than 10 items) the internal consistency of the subscales were assessed using mean inter-particular correlations as recommended by Briggs and Cheek [40]. These ranged from 0.31- 0.forty indicating very skilful internal consistency. The items and reliability statistics of each subscale are shown in Table two.

Total scores for each subscale were calculated by calculation together the scores for the individual items. Loftier scores indicated strong understanding. The subscales generated from the set up of attitudinal items volition be referred to throughout the remainder of this manuscript equally the Birth Attitudes Contour Calibration (BAPS).

Childbirth fright was also measured at xviii -20 weeks, using a Fright of Nascence Scale (FOBS) [29]. Women were asked to respond to the question 'How do yous feel right now about the approaching nascence?' by marking ii 100 mm VAS-scales anchored past the words: worried/ calm, and strong fear/no fright. These ii scores were averaged to give a total score. The FOBS demonstrated splendid internal consistency, with a mean inter-item correlation of 0.84.

The other questions in the questionnaire were fatigued from previous population based studies of women'southward experiences of pregnancy and birth conducted in Commonwealth of australia and Sweden [41, 42]. Five-bespeak Likert scales were used to determine physical health, emotional health and previous birth experience. Women's feelings about the budgeted nascency and the new-born were measured by their response to the questions: "How do you feel nigh the budgeted birth?" and: "How do yous experience when thinking about the beginning weeks with a new-born baby?" Five response alternatives ranged from 'Very positive' to 'Very negative' with a eye option of 'both positive and negative'. Responses to all the Likert scales were dichotomised to reflect 'positive' or 'less than positive'. Birth preferences were ascertained by asking the question "If you had the possibility to choose, how would you adopt to give birth", with the response alternatives 'Vaginal nascence' and 'Caesarean'.

Women were asked at two months postal service partum virtually their mode and experiences of birth. These questions had been previously used in Australian and Swedish studies [41, 42]. They were asked to indicate the length of their labour in hours past answering the question "How many hours did your labour terminal?" Their perception of labour pain was explored by the questions: "How much pain did you feel during labour?" and "How did yous experience this pain?" This was assessed by marker 2 seven betoken scales anchored with the phrases 'no pain at all (one)' to 'worst pain imaginable (7)' and 'Very Negative' (vii) to 'Very Positive' (one).

Analysis

Statistical assay was conducted using SPSS for Windows Chicago, IL, Us Version 17. Characteristics of the women from both cohorts were compared using chi square tests. A cluster analysis was conducted on responses to the BAPS and the level of fright, equally determined by the FOBS [29]. Equally cluster analysis is very sensitive to outliers [43], the data was screened and three outlying cases were identified and removed. These cases contained fearfulness scores at the extreme end of the calibration and 'not idea about' responses to all attitudinal questions. Consistent with the procedures described past Shannon [43], a Kappa-hateful cluster analysis, forcing a iii cluster solution, was applied to z-score transformed responses to each of the four BAPS subscales and the FOBS mean score. Given the exploratory nature of cluster assay other possible solutions (e.chiliad. 2-cluster, 4-cluster solutions) were also inspected. The 3 cluster solution was institute to offer the most interpretable and clinically meaningful solution. Each cluster was named according to the group of its items later on give-and-take and understanding from the authors that these names gave an accurate and easily understood meaning. Demographic characteristics of the iii clusters were compared using chi square statistics.

The adjacent stride was to calculate crude and adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the unlike explanatory variables during pregnancy and nascency using the Mantel–Haenszel technique as described past Rothman [44]. Differences in the continuous data outcome variables measuring length of labour and experience of pain were compared across clusters. Due to unequal group sizes and not-normal distributions this was calculated using the Kruskal Wallis examination [44].

Results

Participation and response

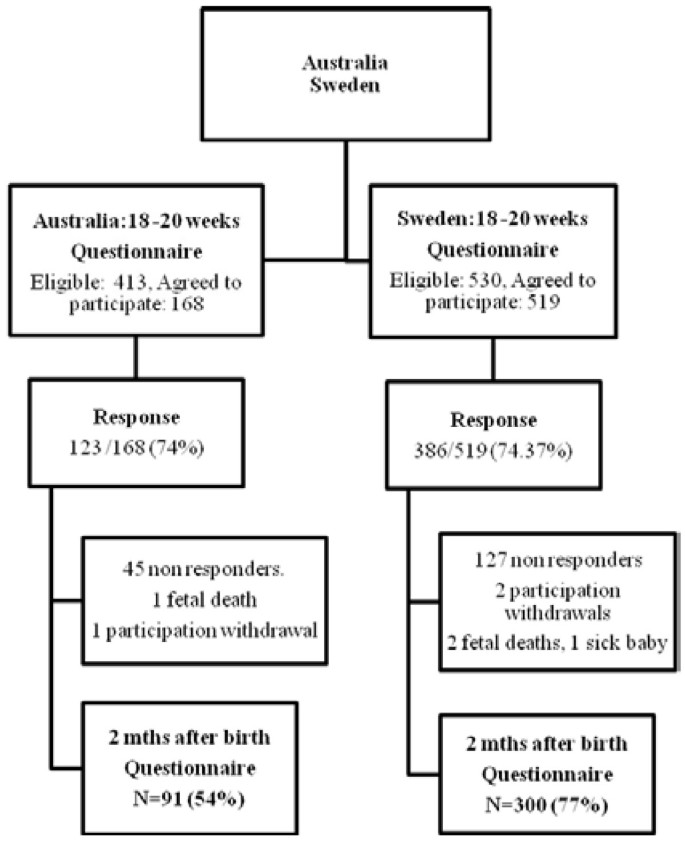

Figure one shows that of the 530 women who were eligible from the Swedish sample, 519 were recruited, (98% of those eligible), 386 women returned the showtime questionnaire giving a response charge per unit of 74%. The Australian sample had 413 women eligible, 168 recruited (41% of those eligible) and 123 returns, making a response rate of 74% for the get-go questionnaire.

Participation and Response Rates.

At 2 months post partum a follow-upward questionnaire was sent to 386 Swedish women, after exclusion of two intrauterine deaths, one very sick baby, ii who withdrew participation and 127 who did not respond to the two get-go questionnaires. 3 hundred post partum questionnaires were completed past the Swedish women. In the Australian cohort the mail service partum questionnaire was sent to 121 women later the exclusion of 45 women who did not respond to the first questionnaire, i foetal death and one participation withdrawal, leaving 91 women who responded.

Sample characteristics

The bulk of women in both countries were 25 to 35 years old, married or cohabiting and were multiparas (Tabular array three). The socio demographic characteristics of both samples did not bear witness whatever statistically meaning differences in historic period, marital status, previous infertility, parity and didactics. The Australian cohort had significantly more women who had experienced a previous caesarean section; both emergency and elective, while the Swedish accomplice had significantly more women who had previously had an instrumental nascence (Table 3).

Cluster analysis

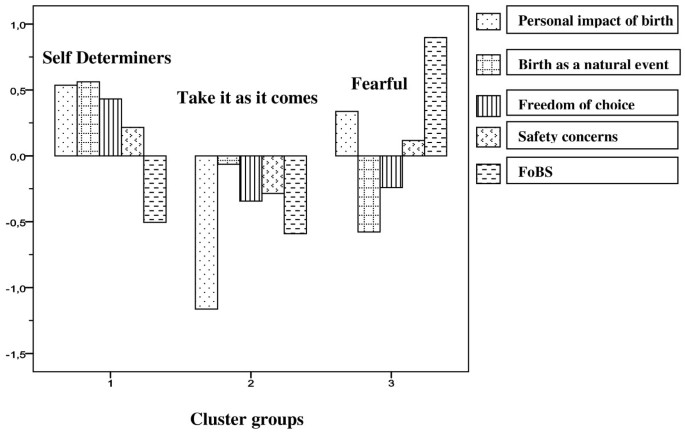

Figure two shows the three clusters which were identified based on women's level of agreement to the BAPS items and their level of fright on the FOBS. Cluster ane 'Cocky determiners' were characterised by low fear and agreement with the attitudes relating to the personal impact of nascence, safety concerns, the natural process of birth and freedom of selection. Cluster 2 'Take it as it comes' were not afraid of childbirth. They indicated low levels of agreement on all attitude items. Cluster iii, the 'Fearful', scored high on childbirth fright, showed moderate agreement to the items regarding the personal impact of birth and some business concern regarding safety. This group reported low levels of agreement with the items relating to the natural process of birth and to exercising gratis choice regarding mode of birth.

Clusters identified from z-score transformed responses to four attitudinal subscales and FoBs mean score.

Characteristics of clusters

Tabular array iv shows that the numbers of women in the Australian cohort were evenly spread across the 'Self determiners', 'Accept it as it comes' and 'Fearful' clusters (32%, due north = 37, 35%, n = 40, 33%, northward = 38 respectively), while the Swedish cohort had a comparatively less balanced membership: 'Self determiners' (42%, n = 155), 'Take it as it comes' (25%, n = 90), and 'Fearful' (33%, n = 121). These differences in state of care on cluster membership did not quite accomplish statistical significance (p < 0.06). The socio-demographic and personal characteristics of each cluster were compared with no differences detected in age, marital status, parity or previous infertility. Women with a lower level of instruction however, were more than likely to belong to the 'Self determiners' cluster (p < 0.003), while women who had experienced a previous caesarean were less likely to belong to this group (p < 0.001). Women with a previous negative nativity feel were more likely to belong to the 'Fearful' cluster (p < 0.001).

After adjustment for historic period, land, education, and parity, Table five shows that the 'Fearful' cluster at eighteen-xx weeks gestation were more likely to take poorer self rated emotional wellness than the women in the 'Self determiners' cluster (OR = 3.3 CI 1.5-7.3). They were more likely to prefer a caesarean (OR = 3.3 CI: i.six-6.eight) and more than likely to have less than positive feelings well-nigh being meaning (OR = iii.half dozen CI: one.4-9.0).This group of women were more likely to study less than positive feelings about the budgeted nascence (OR = 7.ii CI: 4.4-12.0) and twice every bit probable to take less than positive feelings about the first weeks with a newborn (OR = two.0 CI 1.2-three.6).

Tabular array v shows that at mid pregnancy, the 'Have information technology as it comes' cluster had a higher likelihood of having less than positive feelings about the beginning weeks with a newborn when compared with the 'Self determiners' (OR = 2.0 CI, ane.1-three.4) nevertheless this was no longer pregnant when adjusted for age, country, education, and parity.

Nascence outcomes

At two months post partum Table 6 shows that the women classified in the 'Self determiners' cluster had the highest percentage of unassisted vaginal births: 44% (n = 113) compared with 27% (north = 67) in the 'Fearful' and 29% (n = 73) in the 'Take it as it comes' cluster (p <0.04). The 'Fearful' cluster had a greater likelihood of having an elective caesarean (OR = 5.4 CI ii.ane - 14.2) and higher odds of having an epidural if they laboured (OR = ane.9 CI 1.one-3.ii). 'Fearful' women reported a higher likelihood of having received counselling during pregnancy for their fear of nativity when compared with the women in the 'Self determiners' cluster (OR = 5.0 CI 1.ix-13.2). Their likelihood of a negative nascency experience was higher than for the women in the 'Cocky determiners' (OR = 1.7 CI 1.01-2.9). At two months post partum (Table half dozen), the 'Take information technology equally information technology comes' reported three times the likelihood of constituent caesarean OR = three.0 (CI ane.1-viii.0) when compared to the 'Self determiners'.

Afterwards excluding women who had an elective caesarean, hateful scores were calculated on length, intensity and experience of labour pain beyond the clusters. The 'Take it as it comes' cluster reported a shorter length of labour (p < 0.005) than women in the other two clusters (Tabular array 7). The 'Fearful' reported their labour pain equally more intense than women in the other clusters (p <0.009). There was no difference between the clusters in the women's experience of labour hurting.

Discussion

This cohort of Swedish and Australian women were categorised into three attitudinal profiles: 'Self determiners', 'Have it as it comes' and 'Fearful'. Comparing of the women within these clusters revealed differences in emotional health, birth preferences, and feelings about existence pregnant. They also showed pregnant differences in a number of birth outcomes. Of these 3 profiles, the presence of fright had the most negative impact on women's emotional wellness, feelings about pregnancy and parenting and feel of nascence. Belonging to the 'Fearful' cluster increased a woman'southward likelihood of preferring, and actually having, an constituent caesarean.

'Fearful' cluster

The 'Fearful' women were characterised by high levels of fearfulness and concerns regarding safety. These women were worried nearly the personal impacts of birth such every bit pain, their sense of control and any detrimental effects birth may have on their body. These women did not meet birth as a natural consequence and did not subscribe to an attitude of freedom of choice. Their likelihood of preferring a caesarean was three times that of women in the 'Self determiners' cluster. This resonates with the Raphael-Leff's description of the 'Regulator' cluster of mothers [33, 35, 45].

This finding was besides consequent with the results of the Thomas and Paranjothy report [fourteen] which described women who preferred a caesarean as more probable to place a high priority on their own safety and existence as pain costless as possible. As well, Thomas and Paranjothy showed that women [xiv] who preferred caesarean were more likely to disagree with the statement that 'nativity was a natural procedure that should not be interfered with unless necessary' - an attitudinal item included in this 'Fearful' cluster group.

Information technology was not surprising to find that the 'Fearful' cluster contained significantly more women with a previous caesarean and a previous negative birth feel. These are well known determinants of childbirth fear [46, 47]. Belonging to the "Fearful' cluster increased the likelihood of women actualising their preference for an elective caesarean. This college prevalence of elective caesarean has been described in the literature previously on childbirth related fear from the Nordic populations [42].

Women in the 'Fearful' cluster had poorer self rated emotional health in mid pregnancy than women in the other clusters; a finding that points to them beingness at risk of poor mental health both in the perinatal period and possibly beyond [48]. Women with childbirth related fear are afraid of inadequate back up, inability to contribute to important decisions apropos themselves or their baby, losing command and 'performing' desperately [24–28, 31, 46, 47]. These characteristics once more prove similarities with Raphael-Leff's 'regulator' group who see vaginal nascence as a potentially humiliating experience [35].

Fear is commonly articulated as fear of unbearable hurting, fear for their own and their infant's prophylactic and fear of obstetric injuries [47]. Women in this cluster reported more negative birth feel than the other clusters. Possibly inherent in their negative experience of birth, was our finding that the 'Fearful' cluster of women perceived their labour every bit more than painful than the women in the other clusters. Our findings demonstrated that the 'Fearful' cluster had a higher use of epidural. Pain in labour is a complex result. Despite widespread apply of powerful analgesics and modern anaesthetic techniques, many women study loftier levels of pain with some describing it as the 'worst pain imaginable' [49]. Alleviating pain does not guarantee an improvement in women's experience of labour or their longer term recollections of pain [50].

'Cocky determiners' cluster

Overall the 'Self determiners' cluster contained the highest proportion of women. These women showed firm opinions on a range of attitudes and beliefs. They were not afraid of childbirth. These women had the highest percentage of unassisted vaginal birth.

The 'Self determiners' were less educated than women in the other two clusters. This finding is in contrast to the media prototype of the savvy, assertive highly educated adult female belongings clear views about the type of nascency she wants [51]. Likewise it contrasts with the generalisations created by some healthcare professionals who perceive lower educated women as being less informed and less interested in making choices regarding their intendance. Green et al [52] reported that, contrary to the stereotypes of significant women generated by caregivers, the less educated women did not want to mitt over all control to the staff and had the highest expectations for a fulfilling nascence experience Our findings are commensurate with this.

'Take it as it comes' cluster

The women in the 'Take it equally information technology comes' cluster were not afraid of childbirth only they appeared to have no business firm attitudinal preferences concerning birth. The 'Take it as it comes' were no more likely to have preference for either vaginal or caesarean birth than the 'Self determiners', even so when actual mode of birth was compared, the 'Take it as information technology comes' group had an increased likelihood of elective caesarean. We might postulate that these women volition just 'go with the flow' as described past Pilley Edwards [53]. The reluctance of some women to appoint in autonomous obstetric determination-making has been described and explained in regard to actively choosing fashion of birth [38]. Many women feel unable or unwilling to do choice regarding mode of birth as any decision is e'er governed by what is best for the baby in the particular circumstances they discover themselves in [38].

This approach is in keeping with Lehman'south (1950) 'Conclusion Theory' as cited by Lie [54] where "in that location is a certain relationship between a rational person'south preferences for acts, probability assignment for states and utility assignment for consequences [54]". It follows that given most women agree strongly with the paramount importance of safe of the baby, that this 'Have information technology every bit information technology comes' group would exist specially vulnerable to acceding to an intervention that was in any way couched with linguistic communication promoting infant wellbeing. This cluster of women show some characteristics in common with Raphael-Leff's 'reciprocator' orientation who practice not have a precise birth 'plan', instead belongings a 'look-and-see' attitude regarding the childbirth [33].

Clinical implications

Knowing that information shapes beliefs and can lead to mental attitude changes [5, 6], midwives and doctors have an important office in influencing positive, salubrious attitudes to nascence in women by providing clear, prove based data. In caring for women who fit the 'Fearful' cluster the findings of this written report can assistance clinicians to focus on raising give-and-take well-nigh the personal impact of birth. In particular, discussion and planning should address women'southward feelings about control and pain. Debunking myths and providing clear communication nearly hazard and rubber ought to exist a feature of antenatal care. Clinicians accept an opportunity to reinforce the natural aspects of the pregnancy and nascence experience. Understanding the complexities of the underlying attitudes and fears women bring with them to the antenatal come across or birthing room can enable motherhood-care professionals to interact in a sensitive and meaningful way with women.

Midwives and doctors are in a unique position to develop a trusting insightful relationship with the women they encounter. In being aware of women's fears in particular, midwives and doctors then must be sensitive to anxieties which can be approached with reassurance, data and ane to one support. While the role of specific counselling for fear of childbirth has not been shown to 'cure' fear [55, 56] clinicians must remain alert to women with serious distress requiring referral for skilful psychological assistance.

Women in the 'Take it equally it comes' cluster may also warrant further attention from clinicians. This group are most probable the women who antenatally seem to have no issues. This group of women could do good from clear information regarding the potential impacts of intervention on them and their baby. They could be encouraged to take a more proactive approach to giving birth with confident encouragement from their clinician. With clear explanations and guidance from clinicians these women may be potentially positioned to avoid unnecessary intervention.

Limitations

This report focused on women from two regional areas in Sweden and Australia and, every bit such, the findings should be interpreted with some caution in terms of generalisablity to other populations. The potential to discover a divergence in cluster membership by country of care may have been limited by the relatively low numbers of participants in the Australian accomplice. The participation rate in the Australian setting may have been linked to the context of the booking appointment where the women were invited to participate. At this visit the adult female may well take been field of study to information overload equally she is given wellness promotion information, referrals for blood tests, clinic appointments and antenatal education class information. The brunt of completing a questionnaire on acme of this may have been too much for some women.

Additional research is needed on a larger number of women to detect if there are systematic differences between the two countries. Further replication of the results of this study beyond other populations is too needed to confirm their stability, particularly given the exploratory and subjective nature of cluster assay.

Selection bias is a mutual problem in the recruitment of participants to accomplice studies, as is loss to follow up with a longitudinal design. This written report excluded women who were unable to speak the native language of their respective state of intendance and therefore limited the study's capacity to explore a more diverse ready of opinions and attitudes. Both regional centres are yet characterised by depression numbers of strange built-in women.

The BAPS adopted for this written report has shown iv subscales measuring attitudes [39] with skillful internal consistency. The items which found the scale take been used in two previous British studies [14, 38]. Although the use of a defined gear up of attitudes limits our ability to identify other salient beliefs that may exist relevant, it does permit the responses to be scored then amassed and compared beyond groups in a consistent manner. The prospective design of this study ensured that attitudes were measured during pregnancy, thereby avoiding the potential problem with recall bias.

Determination

In this Australian and Swedish study, three clusters of women were identified based on attitudes held during mid pregnancy. Belonging to the 'Fearful' cluster had a negative effect on women's emotional health during pregnancy and increased her likelihood of an operative birth and a negative birth feel. Women in the 'Take it as it comes' cluster were identified as a vulnerable group for an operative birth. The results of this study suggest that attitudes and childbirth related fear are of import factors related to birth outcome that should exist explored by health professionals during the antenatal menses. Midwives and doctors tin can assist women in their preparation for birth by spending time sensitively enquiring about their feelings and attitudes toward pregnancy. Working towards a positive experience of birth is i of the most crucial goals the health team must fix. Almost especially midwives and doctors must hash out any fears the women may have. Knowledge well-nigh women'due south attitudes may help midwives and doctors to tailor their interactions with women in such a way as to inform and reassure them in their chapters to give birth and become a female parent. The use of this profiling approach on a larger cohort of women is recommended for further research.

References

-

Banta D: What is the efficacy/effectiveness of antenatal care and the financial and organizational implications? Regional Office for Europe (Health Evidence Network Report). 2003, WHO, Copenhagen, http://www.euro.who.int/Document/E82996.pdf, accessed [December 1 2011]

-

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: Perinatal Anxiety and Depression(C-Gen 18) College Statement C-Gen 18: Royal Australian and New Zealand Higher of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. 2012

-

Potts Southward, Shields SG: The experience of normal pregnancy: an overview. Women-Centered Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth. Edited by: Shields SG, Candib LM. 2010, Radcliffe Publishing, Oxford

-

Cerebral, affective, and behavioural components of attitudes. Attitude Organisation and Modify: An Assay of Consistency Among Attitude Components. Edited by: Rosenberg MJ, Hovland CI. 1960, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1-14.

-

Fishbein One thousand, Raven B: The AB scales: An operational definition of belief and attitude. Human Relat. 1962, 15 (ane): 35-44. ten.1177/001872676201500104.

-

Harsanyi J: Games with incomplete data played by Bayesian players. Manag Sci. 1967-68, 14: 159-182. 10.1287/mnsc.xiv.3.159. 320 - 34, 486-502

-

Bonanno GF: Information, Knowledge and Belief. Bull Econ Res. 2002, 54: 47-67. 10.1111/1467-8586.00139.

-

Science Daily: University of British Columbia Trio of studies reveals attitudes of women, obstetricians and family physicians on utilize of technology in childbirth. 2011, 13 June [cited 2011 Retrieved July xiii, 2011, from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/06/110613103815.htm]

-

Klein MC, Janusz K, Hearps SJC, Tomkinson J, Baradaran N, Hall WA, McNiven P, Brant R, Grant J, Dore S, Brasset-Latulippe A, Fraser WD: Birth Engineering and Maternal Roles in Birth: Cognition and Attitudes of Canadian Women Approaching Childbirth for the Offset Fourth dimension. J Obstetrics Gynaecol Tin can. 2011, 33 (6): 598-608.

-

Nettleton S: The Sociology of Health and Ilness. 2006, Polity Press, Cambridge

-

Green J, Baston HA, Easton Due south, McCormick F: Greater Expectations ?. Sunmmary Report. Inter-relationships between women's expectations and experiences of determination making, continuity, selection and command in labour,and psychological outcomes. 2003, Mother & Infant Research Unit, Leeds, Availablefrom:http://www.york.air-conditioning.u.k./media/healthsciences/documents/miru/GreaterExpdf.pdf [accessed December 1 2011]

-

Green J, Coupland V, Kitzinger S: National Found for Health and Clinical Excellence : Intrapartum care care of healthy women and their babies dur ing childbirth. Expectations, experiences, and psychological outcomes of childbirth: a prospective study of 825 women. Nascence. 1990, 17 (one): 15-24. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.1990.tb00004.10.

-

Green JM, Baston HA: Take Women Become More Willing to Have Obstetric Interventions and Does This Relate to Mode of Nativity? Data from a Prospective Study. Birth: Issues Perinatal Intendance. 2007, 34 (one): half-dozen-xiii.

-

Thomas J, Paranjothy S: The National Sentinal Caesarean Section Audit Written report. Majestic Higher of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit of measurement. 2001, RCOG Press, London

-

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (Squeamish): Antenatal and postnatal mental health: Clinical management and service guidance. Clinical Guideline No. 47. 2007, National Found for Clinical Excellence (Squeamish, London

-

Austin MP, Highet N, and the Guidelines Expert Advisory Committee: Clinical exercise guidelines for low and related disorders – anxiety, bipolar disorder and puerperal psychosis – in the perinatal period. A guideline for primary intendance wellness professionals. 2011, beyondblue: the national depression initiative, Melbourne

-

Stapleton H: The use of evidenced-based leaflets in materntiy care. Informed choice in Maternity Care. Edited past: Kirkham Yard. 2005, Palgrove McMillan, New York

-

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, SIGN: Postnatal Depression and Puerperal Psychosis: A National Clinical Guideline. 2002, http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/threescore/index.html.[Accessed December xx]

-

SFOG and SBF (The Swedish Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and The Swedish Association of Midwives): Antenatal intendance, sexual and reproductive health. Report No. 59 from the good panel (In Swe) [Mödrahälsovård, Sexuell och Reproduktiv Hälsa]. 2008, SFOG, Stockholm, Sweden

-

Karlström A, Nystedt A, Johansson M, Hildingsson I: Behind the myth - few women prefer caesarean department in the absence of medical or obstetrical factors. Midwifery. 2011, 27 (5): 620-627. ten.1016/j.midw.2010.05.005.

-

Sutherland M, Yelland J, Brown S: Social Inequalities in the Organization of Pregnancy Care in a Universally Funded Public Health Care System. Maternal Child Health J. 2011, sixteen (two): 288-296.

-

Huizink AC, Mulder EJH, Robles de Medina PG, Visser GHA, Buitelaar JK: Is pregnancy anxiety a distinctive syndrome?. Early Human being Dev. 2004, 79 (two): 81-91. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2004.04.014.

-

Hall WA, Hauck YL, Carty EM, Hutton EK, Fenwick J, Stoll K: Childbirth Fright, Anxiety, Fatigue, and Sleep Impecuniousness in Pregnant Women. J Obstetric Gynecol Neonatal Nursing. 2009, 38 (five): 567-576. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01054.x.

-

Zar M, Wijma K, Wijma B: Pre – and postpartum fearfulness of childbirth in nulliparous and parous women. Scand J Behav Ther. 2001, 30 (30): 75-84.

-

Alehagen S, Wijma B, Wijma 1000: Fear of childbirth before, during, and later childbirth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006, 85: 56-62. x.1080/00016340500334844.

-

Kjærgaard H, Wijma K, Dykes AK, Alehagen Southward: Cross-national comparisons of psychosocial aspects of childbirth. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2008, 26 (4): 340-350. 10.1080/02646830802408498. Special Issue

-

Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro Thou, Halmesmaki Due east, Saisto T: Fear of childbirth according to parity, gestational age, and obstetric history. BJOG, Br J Obstetrics Gynaecol. 2009, 116: 67-73. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02002.x.

-

Fenwick J, Chance J, Nathan E, Bayes South, Hauck Y: Pre- and postpartum levels of childbirth fear and the relationship to nativity outcomes in a cohort of Australian women. J Clin Nurs. 2009, 18 (five): 667-677. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02568.ten.

-

Haines H, Pallant J, Karlström A, Hildingsson I: Cantankerous-cultural comparison of levels of childbirth-related fearfulness in an Australian and Swedish sample. Midwifery. 2011, 27: 560-567. 10.1016/j.midw.2010.05.004.

-

Johnson R, Slade P: Does fear of childbirth during pregnancy predict emergency caesarean section?. BJOG: Int J Obstetrics Gynaecol. 2002, 109 (eleven): 1213-1221. 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2002.01351.x.

-

Geissbuehler V, Eberhard J: Fear of childbirth during pregnancy: A study of more than 8000 pregnant women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2002, 23 (4):

-

Lowe NK: Cocky-efficacy for labor and childbirth fears in nulliparous pregnant women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2000, 21 (4): 219-224. 10.3109/01674820009085591.

-

Raphael-Leff J: Psychological Processes of Childbearing. 2009, Anna Freud Centre, London, 4

-

Wiklund I, Edman M, Larsson C, Andolf E: Personality and way of delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006, 85 (x): 1225-1230. x.1080/00016340600839833.

-

Raphael-Leff J: Healthy Maternal Ambivalence. Stud Maternal. 2010, ii: I(I)SSN 1759-0434 2009

-

van Bussel JB, Spitz , Demyttenaere K: Childbirth expectations and experiences and associations with mothers' attitudes to pregnancy, the child and motherhood. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2010, 28 (2): 143-160. x.1080/02646830903295026.

-

Georgsson Öhman S, Waldenström U: 2d-trimester routine ultrasound screening: expectations and experiences in a nationwide Swedish sample. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008, 32: xv-22. ten.1002/uog.5273.

-

Kingdon C, Neilson J, Singleton V, Gyte G, Hart A, Gabbay M, Lavander T: Choice and nascency method: mixed-method written report of caesarean delivery for maternal asking. BJOG: Int J Obstetrics Gynaecol. 2009, 116 (7): 886-895. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02119.10.

-

Haines H, Rubertsson C, Pallant J, Hildingsson I: Womens' attitudes and beliefs of childbirth and association with birth preference: A comparing of a Swedish and an Australian sample in mid-pregnancy. Midwifery. 10.1016/j.midw.2011.09.011. in press. corrected proof

-

Briggs SR, Cheek JM: The office of cistron analysis in the development and evaluation of personality scales. J Personal. 1986, 54: 106-148. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1986.tb00391.x.

-

Dark-brown S, Lumley J: The 1993 Survey of Recent Mothers:Issues in survey design, assay and influencing policy. Int J Qual Health Intendance. 1997, 9: 265-277.

-

Waldenström U, Hildingsson I, Ryding EL: Antenatal fear of childbirth and its association with subsequent caesarean section and experience of childbirth. BJOG: Int J Obstetrics Gynaecol. 2006, 113 (6): 638-646. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00950.x.

-

Shannon WD: Cluster analysis. Handbook of statistics 27: Epidemiology and Medical Statistics. Edited by: Rao CR, Miller JP, Rao DC. 2008, Elsevier, New York, 342-366.

-

Rothman KJ, Greenland S: Modern Epidemiology. 1998, Lippincott- Raven Publishers, Hagerstown, 2

-

Raphael-Leff J: Facilitators and Regulators, Participators and Renouncers: Mothers'and fathers' orientations towards pregnancy and parenthood. J Psychosomatic Obstetrics Gynaecol. 1985, 4: 169-184. 10.3109/01674828509019581.

-

Nilsson C, Lundgren I, Karlström A, Hildingsson I: Self reported fear of childbirth and its association with women's nascence experience and style of commitment: A longitudinal population-based study. Women Birth. 2011, xvi (7): 16-

-

Melender HL: Experiences of fears associated with pregnancy and childbirth. Birth. 2002, 29: 101-111. x.1046/j.1523-536X.2002.00170.ten.

-

Schytt E, Hildingsson I: Concrete and emotional self-rated wellness among Swedish women and men during pregnancy and the first twelvemonth of parenthood. Sexual Reprod Healthcare. 2011, 2: 57-64. 10.1016/j.srhc.2010.12.003.

-

Waldenstrom U, Bergman V, Vasell G: The complexity of labor pain: Experiences of 278 women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 1996, 17: 215-228. 10.3109/01674829609025686.

-

Waldenstrom U, Schytt E: A longitudinal written report of women's memory of labour pain--from 2 months to 5 years later on the nascence. BJOG: Int J Obstetrics Gynaecol. 2009, 116 (4): 577-583. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02020.x.

-

Adams South: Middle-class mothers should be talked out of caesareans. The Telegraph. 2012, Th March 22 2012

-

Green JM, Kitzinger JV, Coupland VA: Stereotypes of childbearing women: a await at some evidence. Midwifery. 1990, half-dozen (3): 125-132. ten.1016/S0266-6138(05)80169-X.

-

Pilley Edwards N: Why can't women only say no. Informed pick in maternity care. Edited by: Kirkham M. 2004, Pagrave Macmillan, New York, 302-1

-

Lie RK: An examination and critique of Harsanyi's version of utilitarianism. Theor Dec. 1986, 21 (1): 65-83. 10.1007/BF00134170.

-

Ryding EL, Persson A, Onell C, Kvist Fifty: An evaluation of midwives' counseling of meaning women in fear of childbirth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003, 82 (1): ten-17. 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.820102.ten.

-

Sydsjö G, Sydsjö A, Gunnervik C, Bladh M, Josefsson A: Obstetric outcome for women who received individualized treatment for fearfulness of childbirth during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011, 91 (1): 44-49.

Pre-publication history

-

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed hither:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/12/55/prepub

Acknowledgements

The women and midwives from Wangaratta & Örnsköldsvik for their time. The County quango of Västernorrland, Sweden, The Swedish Research Quango, Stockholm Sweden, Mid Sweden University, Sundsvall Sweden, The University of Melbourne, University Department of Rural Health, Australia for funding support.

Writer information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

HH, IH conceived of the study, developed the report instrument and undertook data drove. HH participated in the study design, performed information edits and statistical analyses, wrote the draft, and reviewed and finalized the manuscript. IH participated in the study pattern, performed data edits, statistical analyses and edited and reviewed the concluding manuscript. JP participated in the report design, performed data edits, statistical analyses and edited and reviewed the final manuscript. CR participated in the written report design, reviewed the study instruments and edited and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Fundamental Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/two.0), which permits unrestricted utilize, distribution, and reproduction in whatever medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and Permissions

Almost this article

Cite this article

Haines, H.Thousand., Rubertsson, C., Pallant, J.F. et al. The influence of women'due south fear, attitudes and beliefs of childbirth on mode and experience of birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 12, 55 (2012). https://doi.org/x.1186/1471-2393-12-55

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/1471-2393-12-55

Keywords

- Pregnancy

- Attitudes

- Childbirth fearfulness

- Cluster analysis

- Scale

Source: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2393-12-55

0 Response to "Pregnant Women Giving Birth to a Baby Fome the Frunt Vowu"

Post a Comment